The entry for 1588 in the Annals of the Four Masters records that:

In modern Irish this excerpt reads as follows

“Tháinig cabhlach mór ina raibh ocht long scór ó Rí na Spáinne. Deir cuid acu go raibh sé ar intinn acu an cuan a thógáil agus teacht i dtír ar chósta Shasana, dá bhfaigheadh siad an deis. Ach níor tharla sé seo dóibh, mar gur bhuail cabhlach na Banríona leo ar an bhfarraige a ghabh ceithre long; agus bhí an chuid eile den chabhlach scaipthe agus scaipthe feadh chóstaí na dtíortha comharsanachta, eadhon, soir ó Shasana, soir ó thuaidh na hAlban agus iarthuaisceart na hÉireann. Bádh líon mór de na Spáinnigh agus scriosadh a gcuid long go hiomlán sna háiteanna sin. ”

“A great fleet consisting of eight score ships came from the King of Spain. Some say that their intention was to have taken harbour and landed on the coast of England, if they got the opportunity. But this did not happen to them, for they were met on the sea by the Queen’s fleet which captured four ships; and the rest of the fleet was scattered and dispersed along the coasts of the neighbouring countries, namely, to the east of England, the north east of Scotland and the north west of Ireland. Great numbers of the Spaniards were drowned and their ships were totally wrecked in those places.”

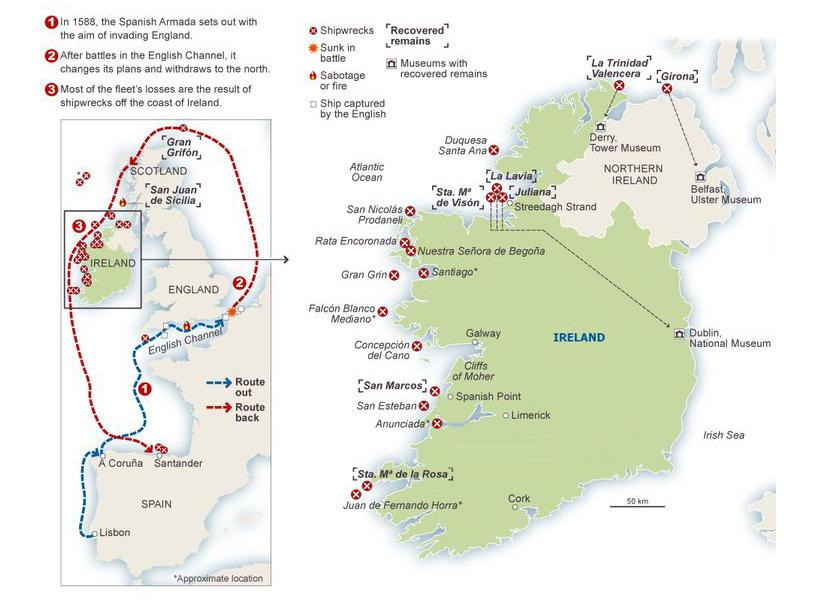

The events described are that of the fleet sent by Philip II 0f Spain, to invade England, known as the Spanish Armada. As described the ships were scattered when the English commander, Admiral Howard, ordered fireships to be sailed into the fleets at anchorage near Calais and Gravelines forcing them into the North Sea by the prevailing winds and having to sail northwards around the northern tip of Scotland and into the Atlantic Ocean and on the 10th of September were struck by a vicious storm which wrecked over twenty seven ships on the west coast of Scotland and Ireland losing an estimated seven thousand sailors and soldiers.

Those survivors of the wrecks in Ireland did not often fair well once reaching land. The Lord Deputy Sir William Fitzwilliam issued a proclamation whereby ‘Harbouring Castaways’ was punishable by death. To his own officers he wrote;

‘Whereas the distressed fleet of the Spaniards by tempest and contrary winds, though the providence of God have been driven on the coast… where it is thought, great treasure and also ordinance, munitions [and] armour hath been cast. We authorize you to… to haul all hulls and to apprehend and execute all Spaniards found there of any quality soever. Torture May be used in prosecuting this inquiry.’

In 1587, as Governor of Fotheringhay Castle, in England, Sir William had supervised the execution of the death sentence on Mary, Queen of Scots.

The Lord President of Connacht Sir Richard Bingham and the Lord President of Munster Sir John Norris enforced this edict in both provinces and most Spanish survivors were hanged when found. In North Connacht many Spaniards survived including a number of about one hundred who were among the four ships wrecked at Streedagh in Co Sligo. Although robbed of their possessions by the local Gaelic population they were allowed to travel to the relative safety of Breffni under the control of Brian O’Rourke the clan chieftain who helped them escape to Scotland. Later he too had to flee to Scotland where he was handed over to the English and hanged at Tyburn in London.

One survivor at Streedagh Captain Francisco de Cuellar wrote a testament to his experiences in Ireland, living for some years along with the McClancy clan of Rossaclogher in modern day Co Leitrim, after he returned to Spain.

Many years later Hugh Allingham, a half brother of the poet William Allingham and an antiquarian whose publications include a history of Ballyshannon in Co Donegal, wrote a book called “Captain de Cuellar adventures in Connaught and Ulster”. Published in 1897 it consists of a translation and commentary of Francisco de Cuellar’s journal of his time in Ireland.

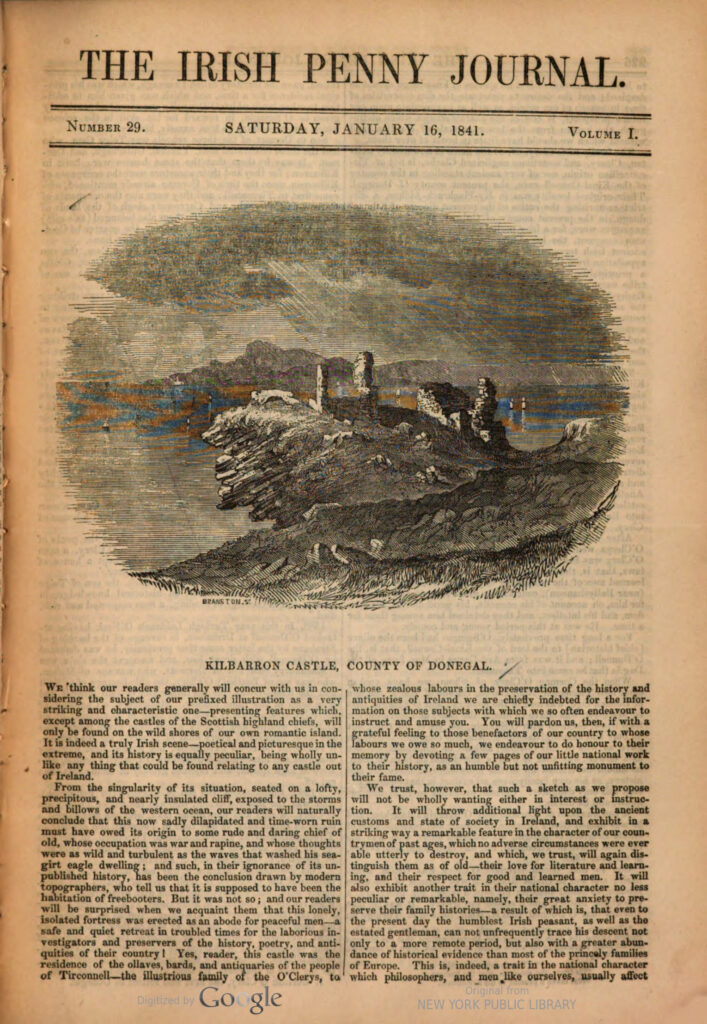

Within the book is an interesting reference to a lock from a Spanish sea chest being found in the vicinity of Kilbarron Castle. It was in the possession of General Tredennick of Woodhill House, Ardara and had originally been identified as the lock of the main door of Kilbarron Castle until correctly been identified by Hugh Allingham who remarked that “this discovery proves beyond question that these chests were in use in Ireland, whether brought over in Spanish or other vessels at a much earlier date than others supposed. The lid found at O’Clery’s Castle, it is reasonable to infer belonged to a chest which was used by the historians of Tyrconnell for the safe keeping of their valuable manuscripts and other articles; and, looking at the fact that their house and property was confiscated within a period of twenty years or so after the Spanish wrecks, and that Kilbarron was plundered and dismantled, there can be no doubt that the chest in question belonged to the period when the O’Clerys flourished in their rock bound fortress”

Hugh Allingham continues “The lid itself offers a curious bit of evidence of its past history: a portion of one of the hinges remains attached showing that it had been wrenched

We can only speculate if this chest came from an armada wreck as these sea chests were available and used by other nations. Apart from the wrecking of three ships at Streedagh, there were others wrecked in west Donegal but the wrecks at Streedagh were closer and presumably flotsam could have been carried into Donegal Bay.

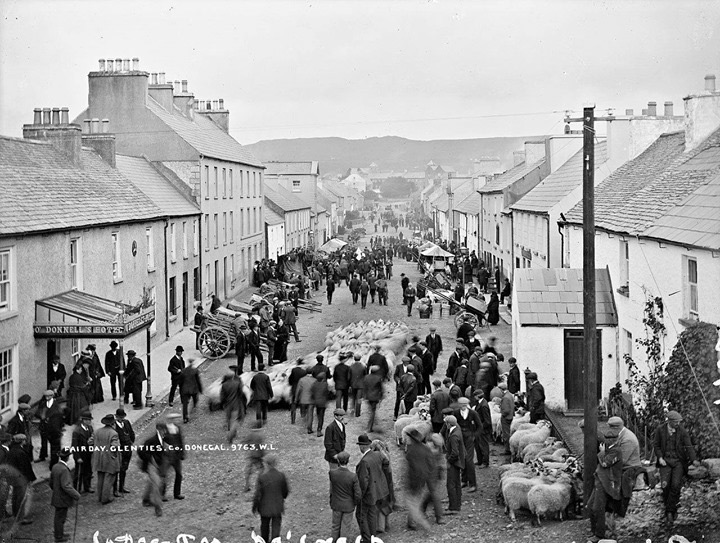

Major General James Richard Knox Tredennick, was a member of the Tredennick family of Camlin Castle between Ballyshannon and Belleek. His older brother the Reverend George Nesbitt Tredennick was the Church of Ireland Rector of Kilbarron parish from 1839 until his death in 1877 and who lived in the Glebe house in Kildoney close to Kilbarron Castle. He also owned Woodhill House in Ardara and willed it to his brother General Tredennick who inherited the property in 1880.

Unfortunately we don’t know if the lock still exists or if it remains at Woodhill house situated near Ardara. General Knox Tredennick’s estate was sold to the Congested Districts Board and offered for sale on the 30th March 1909. The house is currently a guesthouse and restaurant.

Perhaps someone out there knows whatever happened to the lock that was found in the vicinity of Kilbarron Castle?